Apostle of Youth | Christopher Benfey

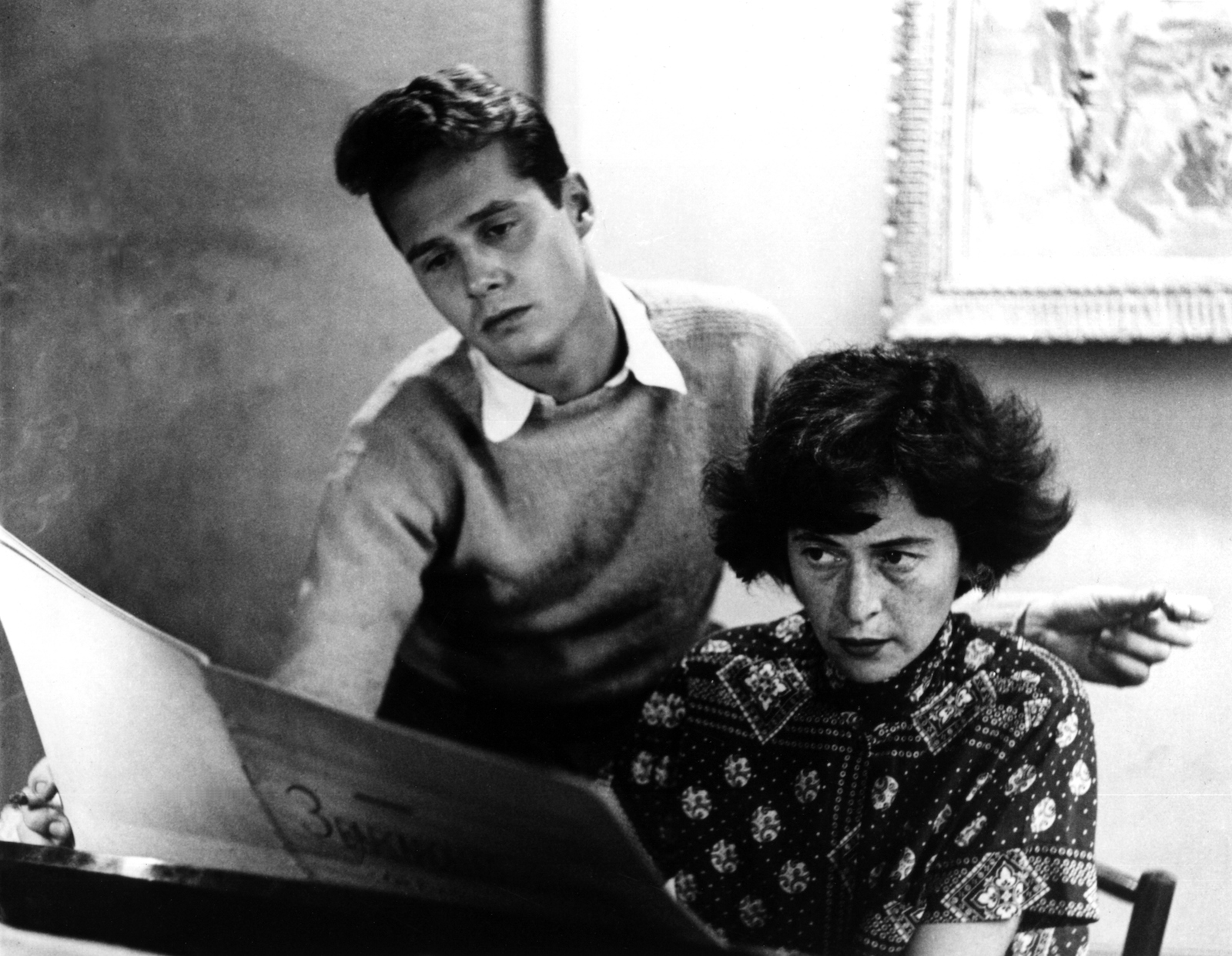

Ken O’Brien/Corbis/Getty Images Ned Rorem and Xenia Gabis, 1950

When I acquired a number of months in the past that the composer and songs critic Ned Rorem experienced died—a lifelong apostle of youth who dreaded turning fifty, he had in some way lived to be ninety-nine—I felt a intricate pang. I very first arrived throughout Rorem’s diary in 1971, when I was a junior at the Putney School, in Vermont. Our Spanish trainer, Emilia Bruce, instructed us to retain diaries in Spanish as element of our common assignments. She advised we could possibly get Anaïs Nin as a model. Consider! I beloved Nin’s diaries. They released me to Henry Miller and Paris and Otto Rank. But typically what I discovered in them was a experience for creating as quick, fragmented, improvisatory—characteristics I nonetheless value in my individual operate and in that of others.

Seeking for comparable publications in the Putney library I arrived across Rorem’s Paris Diary—first posted, like Nin’s opening quantity, in 1966—festooned with his handsome, evergreen encounter. I liked Rorem’s diary for some of the exact explanations I favored Nin’s. For a straight sixteen-year-aged like me, these writers wrote about intercourse with a particular unique latitude. But while Nin’s crafting was cerebral and off-putting—“No excellent enjoy could get location in this wombless femininity,” she wrote of the homosexual poet Robert Duncan—Rorem famously explained an avid gay daily life with aplomb.

In the many years due to the fact, Rorem has felt like a element of my existence, a part of my feeling of myself, for a number of causes. For one particular factor, we arrived from the similar Rust Belt city of Richmond, Indiana. Both of those of our fathers taught at Earlham Higher education, a Quaker school, his in economics (Clarence Rufus Rorem’s later on perform in the economics of health treatment influenced the improvements of Blue Cross Blue Protect) and mine in natural chemistry. “We had been Quakers of the intellectual rather than the puritanical wide variety,” Rorem writes in The Paris Diary, which looks accurate of my family, too. However a technology aside, we were introduced up with the very same procedures: “As Quakers we under no circumstances employed to stand for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’” Me neither. Searching for children’s items with Stephen Spender, a pacifist, Rorem was stunned that Spender acquired toy pistols. “We were being never allowed guns.” My mom and dad only relented when they discovered toy guns with UN Peacekeeping’s blue insignia.

Quakerism, as Rorem’s diary makes clear, is an orthodoxy like any other. Its demanding tenets—nonviolence, rejection of official oaths and pledges, the Inner Light—are hid beneath a veil of silence and a distaste for ritual. Individuals who appear to Quakerism late, attracted by its progressive political tendencies or its reticent creed, are at times stunned to discover that Quakers are, God enable us, Christians. Rorem, who preferred to consume (“I’ve spent a third of my lifetime in slumber, a 3rd in consume, a 3rd vomiting”), in contrast Quaker expert services, “in sort and written content,” to AA conferences. He also likened them to Turkish baths as internet sites of “silent conference,” although in the baths “the silence is shared exclusively by guys, adult men who occur uniquely together not to communicate but to act.”

I initial listened to Rorem’s tunes at the Quaker faculties I attended, Earlham and Guilford, and then in New York throughout the 1980s, and I preferred it for some of the very same qualities—its immediacy, its psychological openness, its private touch—that drew me to his crafting. Rorem composed in many kinds, but he was a learn, like those people other Hoosier songbirds Hoagy Carmichael and Cole Porter, of environment lyrics to songs. “Any excellent track,” he wrote in The Paris Diary, “must be of higher magnitude than both the terms or new music by yourself.” I nevertheless choose Rorem’s options of Emily Dickinson poems—clear, poignant, not seeking to do much too much—to individuals of much more “advanced” composers like Paul Hindemith and Rorem’s sometime mentor Aaron Copland, which seem overbearing and suffocating for the oddly angled lyrics.

Hiroyuki Ito/Getty Visuals Ned Rorem accompanying the Saint Thomas Choir on piano, executing his tunes at St Thomas Church, New York City, October 2003

Rorem considered in giving text and melody a prospect to breathe, and decried (a tiny crankily) the inclination among his intellectual contemporaries to address the voice “not as an interpreter of poetry—nor even essentially of words—but as a system, generally electronically revamped.” He considered the Beatles (whom he in contrast favorably, in a intelligent essay in this magazine in 1968, to Schumann and Poulenc) and Billie Holiday break offered a much better path to a musical foreseeable future than the educational avant-garde of Pierre Boulez. “The Beatles’ words and phrases,” he famous, “often go against the music (the crushing poetry that opens ‘A Day in the Life’ intoned to the blandest of tunes).” As however to illustrate the level, Rorem composed two sharply divergent options—one wistful and resigned, the other percussive and strident—of Dickinson’s quatrain “Love’s stricken ‘Why.’”

I encountered Rorem’s operatic variation of Our City (composed when he was eighty-two) when I was writing an essay about Thornton Wilder’s modernist masterpiece, a perform disguised as a sentimental slice of Americana. Emily Webb has constantly appeared to me an obvious cousin of Emily Dickinson, just one of Wilder’s preferred poets. In the setting of her emotionally too much to handle aria in the Grover’s Corners graveyard, in J. D. McClatchy’s libretto, Rorem found a kindred poignancy, plaintive and intestine-wrenching, to Dickinson’s “stricken ‘why.’” “Goodbye to ticking clocks, to Mama’s hollyhocks,” Emily sings, “to coffee and food, to gratitude.”

I saw Rorem the moment, in Greensboro, North Carolina, when the Jap Music Competition showcased just one of his parts. He was sporting, if I bear in mind right, a dazzling red shirt and a white jacket and he appeared, as normal, dazzling. “Famous final text of Ned Rorem,” he wrote in The Paris Diary, “crushed by a truck, gnawed by the pox, stung by wasps, in dire agony: ‘How do I search?’”